ISSUE #1

DESPELOTE

INTERVIEW

Oliver Jameson

IMAGES

Julián Cordero +

Sebastián Valbuena

Julián Cordero knows that soccer is really about people.

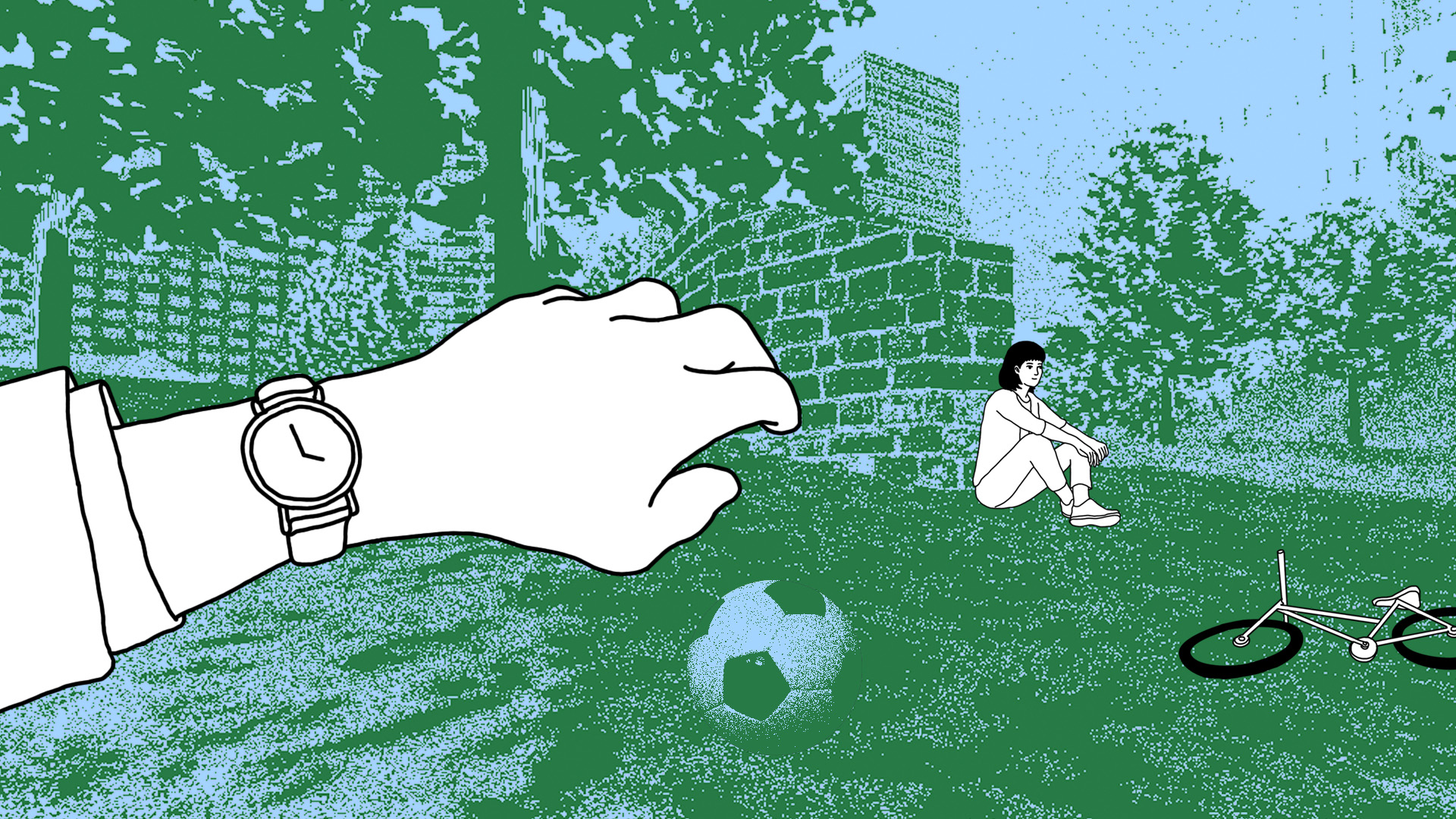

Alongside artist and fellow Quito native Sebastián Valbuena, the New York-based game designer is crafting the world of despelote; a non-competitive soccer game that uses the sport’s human side to paint an intimate portrait of the Ecuadorian capital.

In this story, the city itself is a protagonist. Texture projection techniques bring the real architecture of Quito into despelote’s world, whilst improvised dialogue captures its voices and conversations.

Set in a hazy duotone, these real-world spaces play host to a story of childhood at a time of national fervour surrounding Ecuador’s first ever qualification for World Cup in 2002. This sporting and cultural moment acts as a backdrop for a narrative that delicately recognises that the most popular sport on earth isn’t strictly a spectacle of twenty-two people, on grass, in a stadium.

Rather, the rumblings of conversation in the street, children chasing a ball—or something else kickable—in the local park and the real-time forming of human connections through running, playing and being together are soccer too. These human qualities are as much a part of the ubiquitous culture of the sport as the winning goal watched by millions in the World Cup final.

PLAYSTYLE

What is your personal history with soccer?

JULIÁN CORDERO

I grew up in Ecuador, where the soccer culture is very strong and pretty much everyone has to play it at some point. I loved it when I was growing up. I still love it, but back then, the act of ‘play’ was synonymous with playing soccer. I was also quite good at it. I played in various youth teams and was able to make a lot of friends through it, partly because people respected me for it. I also loved watching and talking about it. It was always the topic I knew I had in common with anyone I met—well, mainly all the guys I would meet.

I then moved to New York City for school. Soccer is not nearly as culturally present in the US as it is in Latin America, and it made me take a step back from it. This distance made me engage with it in a new, more critical way; I became interested in wanting to understand the role soccer has in my life, and how being around it shaped me. I realised I was interested in the culture of soccer, how kicking a ball around acts as a universal language between people.

I was also curious about how people still feel excluded from it even though it is one of the most accessible sports. I didn’t think many games actually focus on the culture of soccer, so I wanted to make one that does, using it as a lens to examine a community, its social dynamics and my own life.

When I started making despelote I decided I was going to start playing pickup games every week, to be constantly thinking about it and exposed to it. Unfortunately, on my second outing, I broke my knee and couldn’t play for two years. I’m finally back to playing now, but I’m sure that had a big influence on what the game has become. I’m just not sure how yet!

What is your personal history with soccer?

JULIÁN CORDERO

I grew up in Ecuador, where the soccer culture is very strong and pretty much everyone has to play it at some point. I loved it when I was growing up. I still love it, but back then, the act of ‘play’ was synonymous with playing soccer. I was also quite good at it. I played in various youth teams and was able to make a lot of friends through it, partly because people respected me for it. I also loved watching and talking about it. It was always the topic I knew I had in common with anyone I met—well, mainly all the guys I would meet.

I then moved to New York City for school. Soccer is not nearly as culturally present in the US as it is in Latin America, and it made me take a step back from it. This distance made me engage with it in a new, more critical way; I became interested in wanting to understand the role soccer has in my life, and how being around it shaped me. I realised I was interested in the culture of soccer, how kicking a ball around acts as a universal language between people.

I was also curious about how people still feel excluded from it even though it is one of the most accessible sports. I didn’t think many games actually focus on the culture of soccer, so I wanted to make one that does, using it as a lens to examine a community, its social dynamics and my own life.

When I started making despelote I decided I was going to start playing pickup games every week, to be constantly thinking about it and exposed to it. Unfortunately, on my second outing, I broke my knee and couldn’t play for two years. I’m finally back to playing now, but I’m sure that had a big influence on what the game has become. I’m just not sure how yet!

PS

The culture surrounding soccer is ubiquitous in many countries, yet most representations in games focus purely on the sport and its rules. How are you doing things differently in despelote?

JC

When you play a game like FIFA, you embody all the superstar players who are supposed to represent soccer in its ‘ideal’ form. It’s cool and exciting, but it isn’t what playing soccer looked like to me growing up. With despelote, we are much more interested in making you feel like a kid who is learning how to kick a ball and trying to make friends, rather than making you feel like Cristiano Ronaldo.

We’re interested in how soccer adapts to any kind of environment and how sometimes, it’s more fun to kick a bottle around on a busy street than a perfect ball in a huge stadium. I believe all of those things tell a much better story of what the sport is, because it tells a story about the people who play it.

PS

Would you consider the city of Quito a protagonist of the game?

JC

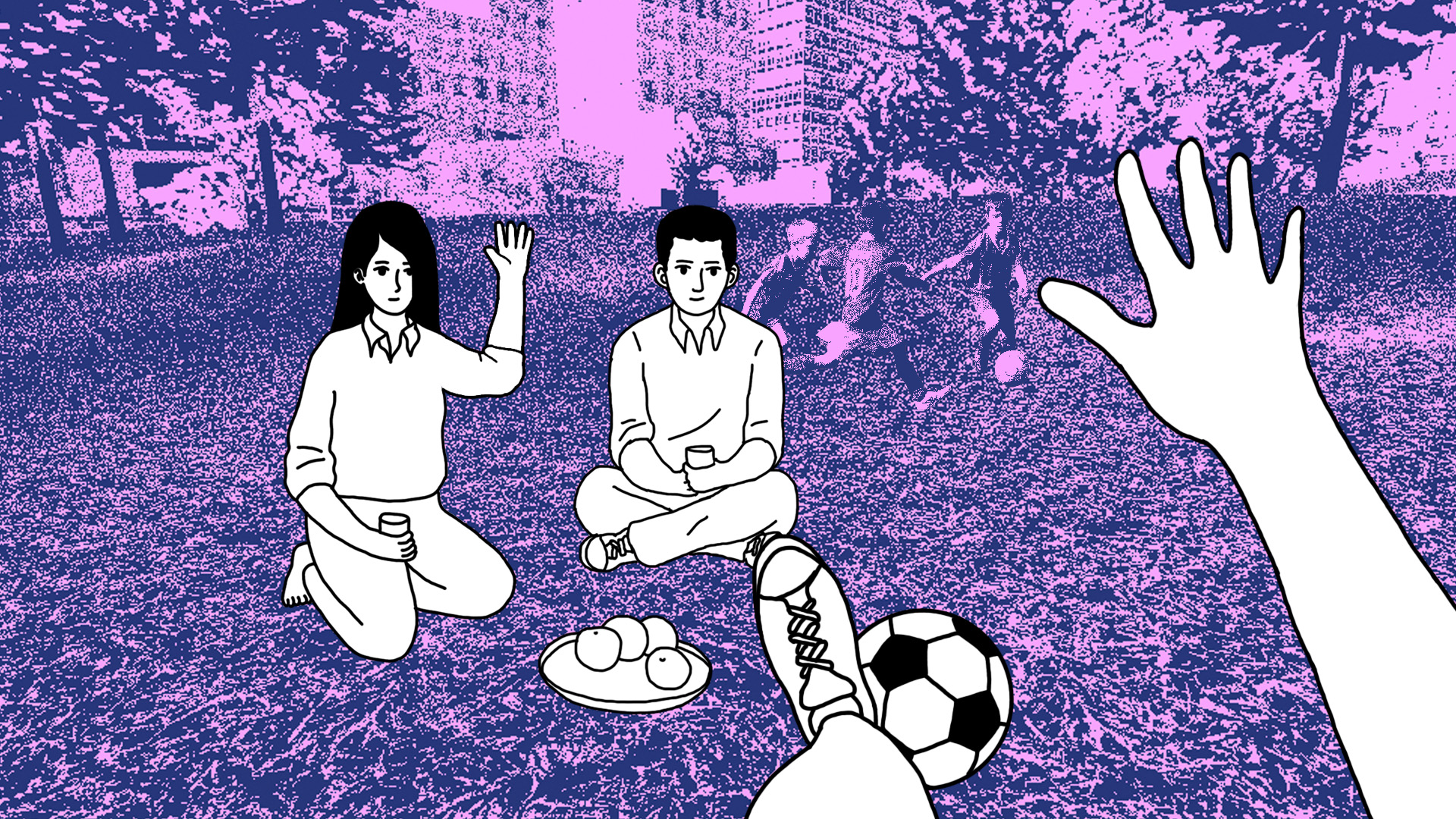

Oh yeah. It was clear from very early that the game would be set in Quito, since Sebastián and I both grew up there and my understanding of soccer was always filtered through that city. We found that the best way to depict it for us was to try to source many of our assets from real life places, so we’ve just been making models from grainy pictures and putting them in our grainy game. We like this approach because it gives these places a nostalgic feel.

Also, none of the dialogue in the game is written—it’s all improvised by friends and family. We’re trying to capture the most genuine conversations as we can and placing them everywhere around the park, so that you slowly absorb the place and its people while you’re kicking the ball around.

The culture surrounding soccer is ubiquitous in many countries, yet most representations in games focus purely on the sport and its rules. How are you doing things differently in despelote?

JC

When you play a game like FIFA, you embody all the superstar players who are supposed to represent soccer in its ‘ideal’ form. It’s cool and exciting, but it isn’t what playing soccer looked like to me growing up. With despelote, we are much more interested in making you feel like a kid who is learning how to kick a ball and trying to make friends, rather than making you feel like Cristiano Ronaldo.

We’re interested in how soccer adapts to any kind of environment and how sometimes, it’s more fun to kick a bottle around on a busy street than a perfect ball in a huge stadium. I believe all of those things tell a much better story of what the sport is, because it tells a story about the people who play it.

PS

Would you consider the city of Quito a protagonist of the game?

JC

Oh yeah. It was clear from very early that the game would be set in Quito, since Sebastián and I both grew up there and my understanding of soccer was always filtered through that city. We found that the best way to depict it for us was to try to source many of our assets from real life places, so we’ve just been making models from grainy pictures and putting them in our grainy game. We like this approach because it gives these places a nostalgic feel.

Also, none of the dialogue in the game is written—it’s all improvised by friends and family. We’re trying to capture the most genuine conversations as we can and placing them everywhere around the park, so that you slowly absorb the place and its people while you’re kicking the ball around.

PS

Which artists are important to you?

JC

The filmmaker Alfonso Cuarón has been a big influence on the project. I’ve also been into Masahisa Fukase’s photography lately and have been reading a lot of Roberto Bolaño. They’re not my favourite artists but they have definitely been important to me lately and probably for the project too.

PS

What does the future of games look like?

JC

I’m excited about a future where technologies that capture the world in new ways—like photogrammetry, motion capture, etc—are not used to achieve the ‘photorealistic dream’, but are used to capture the idiosyncrasies of human behaviour that are impossible to recreate from sitting at a computer.

Which artists are important to you?

JC

The filmmaker Alfonso Cuarón has been a big influence on the project. I’ve also been into Masahisa Fukase’s photography lately and have been reading a lot of Roberto Bolaño. They’re not my favourite artists but they have definitely been important to me lately and probably for the project too.

PS

What does the future of games look like?

JC

I’m excited about a future where technologies that capture the world in new ways—like photogrammetry, motion capture, etc—are not used to achieve the ‘photorealistic dream’, but are used to capture the idiosyncrasies of human behaviour that are impossible to recreate from sitting at a computer.